I've been back from India for only a week, and I've already been back in an airplane twice. But Orange County, CA and Tucson, AZ are hardly as exhilarating as where I've been the past two months.

This is the life I've lived for 24 years: wide freeways, big cars, three-story houses, discount warehouses, central air conditioning, multiple cars, pressurized tap water, expensive pet food and services, excellent customer service, and so on. This is the life I'm used to...it's perfectly normal for me. Yet, as usual after a trip to a developing area, I feel very cynical about my surroundings and myself.

How much plastic waste do I generate shopping at Trader Joe's (as much as I adore it)? How much water do I waste when I make use of the wonderful, hot water that bursts out of the tap? How much extra food do I eat out of boredom? How much energy do I waste running on a belt at the gym for 45 minutes, spending so many calories but accomplishing nothing, for no one? How much gas do I waste satisfying my every whim and fancy, traveling wherever I want to go all by myself in my very own gas-guzzling car?

Ouch. I probably sound really cynical, and right now, I am. Some would calls this "reverse culture shock," which is probably self-explanatory. It means that after the shock of getting used to Indian culture, I'm having trouble adjusting to my own (former, pre-existing) way of life. I thought that was silly--it can't be that difficult to bounce back to the life you've been living for 24 years (give or take several weeks of travel a year)--but it actually is.

India had a great impact on me. I made connections, thanks to CFHI, with several NGOs that with God's help, I hope to revisit one day. I'd like to establish a care home or a clinic of my own there one day, and slowly but surely build it up and more importantly build up the human capacity to sustain it. Eventually, after it's self-sufficient, I will simply be a frequent visitor, a benefactor, a consultant. I will have moved on to the next project, training new people to care for their communities. It's a dream.

Meanwhile, does it make a difference to the pollution-filled beaches I saw in Mumbai, whether or not I recycle my thin plastic goods? I don't know. But I'm going to keep pushing myself to remember what I experienced in the old country, and to change my actions to reflect a better appreciation of the impact of less fortunate circumstances. Because it's not just the poor countries and the rich countries for themselves these days. What we do affects everyone. And even now, even with our botched foreign policy and inadequate homeland security, nowhere is the previous maxim more true than in the U.S. That comes from the mouths of Indians.

Friday, July 20, 2007

Friday, July 13, 2007

The end of my adventures (well, 2007's, anyway)

I'm sitting in the Delhi airport waiting for my flight to Taiwan. It hasn't really struck me that this adventure of almost two months is pretty much over. I am already itching for the next journey, not just the next public health adventure, but also my next trip to the motherland.

Completing my clinical hours for the MPH degree has opened up another world for me. When I was in class, I was always painfully aware that all that book learning gave me only a lopsided view of what it means to be a public health worker. Now I know better.

What does it entail, then? Well, during my clinical hours here in India, I saw that being a social worker/public health worker means being a teacher, a mother, a friend, a coach, and an entertainer. It requires you to sing songs to make friends with grubby kids. It requires you to teach the alphabet to and play Simon Says with middle-aged addicts. It requires you to stretch yourself so you inhabit a world that may be foreign to you, but that is everything to the people you are working with. That world is what they have; you must, in some way, own it too.

I keep telling myself that I don't need to travel halfway across the world to do this, to connect with people who need me, whose warmth and openness are probably a result of the simple, barebones lives they lead. There is plenty of field work right in my backyard, plenty of work for me to roll my sleeves up and get dirty for, which is what I like to do. I guess discovering this about myself reassures me that I've chosen the right career path for myself; being a public health worker (and I consider physicians to be public health workers, in some sense) is front line work.

Sometimes I wonder whether my experiences abroad (in Ecuador and India, to be specific) are really going to be useful to my future "target populations". I'm not sure if they will be. Could I see myself singing to addicts at a de-addiction center in the United States? Would they even respond to that? The American in me is dubious, but the human in me says why not? People are people, and perhaps there are some aspects of other cultures that could enhance my work at home in the U.S. Perhaps my parents' culture is protective against public health menaces (I think in some ways it is, but that's another post). But it's not just that. I hope to revisit the places I saw here in Bharat when I have more skills to offer. By God's grace, I've built a bridge now for myself, made contacts and put names, faces, and organizations on my internal map in a way that I'd never done before, not even in Ecuador.

Now if I could just learn Hindi!

Completing my clinical hours for the MPH degree has opened up another world for me. When I was in class, I was always painfully aware that all that book learning gave me only a lopsided view of what it means to be a public health worker. Now I know better.

What does it entail, then? Well, during my clinical hours here in India, I saw that being a social worker/public health worker means being a teacher, a mother, a friend, a coach, and an entertainer. It requires you to sing songs to make friends with grubby kids. It requires you to teach the alphabet to and play Simon Says with middle-aged addicts. It requires you to stretch yourself so you inhabit a world that may be foreign to you, but that is everything to the people you are working with. That world is what they have; you must, in some way, own it too.

I keep telling myself that I don't need to travel halfway across the world to do this, to connect with people who need me, whose warmth and openness are probably a result of the simple, barebones lives they lead. There is plenty of field work right in my backyard, plenty of work for me to roll my sleeves up and get dirty for, which is what I like to do. I guess discovering this about myself reassures me that I've chosen the right career path for myself; being a public health worker (and I consider physicians to be public health workers, in some sense) is front line work.

Sometimes I wonder whether my experiences abroad (in Ecuador and India, to be specific) are really going to be useful to my future "target populations". I'm not sure if they will be. Could I see myself singing to addicts at a de-addiction center in the United States? Would they even respond to that? The American in me is dubious, but the human in me says why not? People are people, and perhaps there are some aspects of other cultures that could enhance my work at home in the U.S. Perhaps my parents' culture is protective against public health menaces (I think in some ways it is, but that's another post). But it's not just that. I hope to revisit the places I saw here in Bharat when I have more skills to offer. By God's grace, I've built a bridge now for myself, made contacts and put names, faces, and organizations on my internal map in a way that I'd never done before, not even in Ecuador.

Now if I could just learn Hindi!

You Gotta Follow Through

Okay, I admit it. It was an amateur mistake to believe that things would go smoothly when I found a donor to buy an x-ray machine for one of the care homes we visited in Delhi. But it seemed so simple. Wire the money to the NGO spearheading the project, and they buy the machine they expressed a dire need for. Simple, right?

Wrong. And now I'm kicking myself for it because one of the major themes of my two months learning about social work/public health here in India is that follow-through is severely lacking. Yet, I feel personally affronted by this (probably predictable) episode.

To give the care home people the benefit of the doubt, it is possible that what they say is true. They claim that now that this large sum of money has come to them, there are even more pressing and more basic needs than an x-ray machine, one of which is an "auto-analyzer" (I don't know what that is but hey, I'm not a doctor yet). This is plausible. When an NGO starved for funds and always scraping to make ends meet suddenly comes into thousands of US dollars (which goes a LONG way in my mother country), lots of needs compete for those funds. Perhaps something beat out the x-xray machine...like the auto-analyzer?

Either way, it's a shady business. I appreciate the fact that the director of the care home emailed me to notify me that the money would be used in a different way. When lives are hanging in the balance, it is important to think very carefully of how to manage limited funds. Who am I to argue? But at the same time, donors have a responsibility and a right to figure out where there money is going, and when it is earmarked for a specific project, it should go there. If it's not going to go to the project you were campaigning for to begin with, don't bother telling donors what exactly you're going to do with their money...be vague enough to end up telling the truth no matter where the funds end up going.

Not surprisingly, I don't agree with the new trend of NGO online stores that let donors purchase a heifer (or a share of a heifer), or two square kilometers of irrigated land, or a can of worms for fishermen. You probably know which organizations I'm referring to. The first time I bought a basket of chicks, I really thought that my money would go to buy several baby chicks that would be delivered to a family in need. After close inquiry, I discovered that was not the case. Rather, the lady I spoke to informed me that the basket of chicks was merely representative of the sort of thing that would be done with my funds. In reality, it was possible that my money would go to administrative costs, or some other vague necessity (not that I'm against donating money for that, these NGOs have to pay salaries and overhead somehow and that's a good cause too).

Anyway, what I'm getting at here is something else. I'm not here to complain about corruption or laziness among NGOs. I'm here to say that what I've learned here in India, big-time, is that as a public health worker, I MUST be the one to follow through. If I want to come to this country and help, the first thing I need to do is make a TIME COMMITMENT. Why didn't I go and pick out that x-ray machine myself? Because I didn't have enough time. How bad is that? If I really wanted to help, and not do a 99/100 as Paul Farmer calls it (almost, but not quite, accomplishing a necessary task), I would have ensured that the money was used wisely by putting my own sweat and blood into it.

God willing, that's exactly what I intend to do from now on. Let this be a lesson.

***Update: I called up the care home today, to inquire about what happened with the donated money. Apparently, there had been some miscommunication initially, and all along, it was an auto-analyzer, not an x-ray machine, that had been needed. As luck would have it I came down with my second case of mild food poisoning last night, so I wasn't up to schlepping around (it's at least a 45-minute drive) in the Delhi heat. I talked to the workers there, and they assured me that the auto-analyzer had been bought, and it was greatly needed. It apparently allows them to run 300 lab tests a day, and is useful for all patients, whereas the x-ray machine would have benefited only possible TB patients (a large percentage of HIV/AIDS patients, but not ALL of them).

I still have some questions. For example, there are only 26 beds in the care home; do they really need the capacity to do 300 lab tests a day? I'm not questioning their needs, simply trying to be a responsible donor. If one of the major problems with public health today is lack of leadership and management, I figure I have to do my part by seeing things through to the end.

Wrong. And now I'm kicking myself for it because one of the major themes of my two months learning about social work/public health here in India is that follow-through is severely lacking. Yet, I feel personally affronted by this (probably predictable) episode.

To give the care home people the benefit of the doubt, it is possible that what they say is true. They claim that now that this large sum of money has come to them, there are even more pressing and more basic needs than an x-ray machine, one of which is an "auto-analyzer" (I don't know what that is but hey, I'm not a doctor yet). This is plausible. When an NGO starved for funds and always scraping to make ends meet suddenly comes into thousands of US dollars (which goes a LONG way in my mother country), lots of needs compete for those funds. Perhaps something beat out the x-xray machine...like the auto-analyzer?

Either way, it's a shady business. I appreciate the fact that the director of the care home emailed me to notify me that the money would be used in a different way. When lives are hanging in the balance, it is important to think very carefully of how to manage limited funds. Who am I to argue? But at the same time, donors have a responsibility and a right to figure out where there money is going, and when it is earmarked for a specific project, it should go there. If it's not going to go to the project you were campaigning for to begin with, don't bother telling donors what exactly you're going to do with their money...be vague enough to end up telling the truth no matter where the funds end up going.

Not surprisingly, I don't agree with the new trend of NGO online stores that let donors purchase a heifer (or a share of a heifer), or two square kilometers of irrigated land, or a can of worms for fishermen. You probably know which organizations I'm referring to. The first time I bought a basket of chicks, I really thought that my money would go to buy several baby chicks that would be delivered to a family in need. After close inquiry, I discovered that was not the case. Rather, the lady I spoke to informed me that the basket of chicks was merely representative of the sort of thing that would be done with my funds. In reality, it was possible that my money would go to administrative costs, or some other vague necessity (not that I'm against donating money for that, these NGOs have to pay salaries and overhead somehow and that's a good cause too).

Anyway, what I'm getting at here is something else. I'm not here to complain about corruption or laziness among NGOs. I'm here to say that what I've learned here in India, big-time, is that as a public health worker, I MUST be the one to follow through. If I want to come to this country and help, the first thing I need to do is make a TIME COMMITMENT. Why didn't I go and pick out that x-ray machine myself? Because I didn't have enough time. How bad is that? If I really wanted to help, and not do a 99/100 as Paul Farmer calls it (almost, but not quite, accomplishing a necessary task), I would have ensured that the money was used wisely by putting my own sweat and blood into it.

God willing, that's exactly what I intend to do from now on. Let this be a lesson.

***Update: I called up the care home today, to inquire about what happened with the donated money. Apparently, there had been some miscommunication initially, and all along, it was an auto-analyzer, not an x-ray machine, that had been needed. As luck would have it I came down with my second case of mild food poisoning last night, so I wasn't up to schlepping around (it's at least a 45-minute drive) in the Delhi heat. I talked to the workers there, and they assured me that the auto-analyzer had been bought, and it was greatly needed. It apparently allows them to run 300 lab tests a day, and is useful for all patients, whereas the x-ray machine would have benefited only possible TB patients (a large percentage of HIV/AIDS patients, but not ALL of them).

I still have some questions. For example, there are only 26 beds in the care home; do they really need the capacity to do 300 lab tests a day? I'm not questioning their needs, simply trying to be a responsible donor. If one of the major problems with public health today is lack of leadership and management, I figure I have to do my part by seeing things through to the end.

Saturday, July 7, 2007

Right in my backyard: Dharavi, a US $665 million industry (and Asia's biggest "slum")

Two days ago, thanks to Sej's thorough research on Bombay last year, I went on a tour given by a company called Reality Tours and Travel. The tour was not of Colaba, or Haji Ali Pier, or the Gateway of India, but of Dharavi, the place famously known as Asia's biggest slum.

Sej and I had been looking forward to going on this tour for months (no worries, she vows to see it next time). We knew it was not just a slum, but an area buzzing with industry. The combination of poverty (or low income) and industry is particularly interesting to us as public health enthusiasts.

I met Davindra, my tour guide, at the Mahim train station in Bombay. I had no idea where we were going, but it turned out that the station was merely a meeting place; Dharavi is within minutes of Mahim.

Davindra is a slight teenager from a Gujarati family. He immediately tells me that he lives in Dharavi. He's studying "b comm" which will earn him a bachelors in business (commerce). He is the eldest of four children, and his three siblings are girls. When I recount these facts to my aunt, with whom I'm staying not twenty minutes from Dharavi (but worlds apart), she and her friend cluck sympathetically for Davindra's parents, who have been saddled with the financial responsibility of three girls.

But this tour isn't about Davindra, as curious as I am to know about his life. He's very knowledgeable about Dharavi; he was picked and trained by the travel agency for his friendliness and relative ease with the English language.

While many people call Davindra's home a slum, it's really not (and he is quick to tell me so). Dharavi takes up 432 acres of land in an excellent location of Bombay, close to the financial sector and the residential sector, as well as the seaface. There are officially (read: government-recognized) about 60,000 families living here, but the true number, Davindra says, is actually 900,000.

We make our way to the rooftop of one of the slum buildings, where plastic waste is being melted and reformed into little green pellets to sell as raw material. I see groups and groups of people on each roof, working with plastics, socializing, looking at us...everyone doing something. No one is sitting idle.

Davindra tells me as we survey all the activity around us that Dharavi is currently being threatened by a bid to turn the area into a special economic zone. Will it happen, I ask? He has no idea, but tells me that while the government promises to relocate families, it will be difficult (to say the least) for all these workers to shift their businesses and families to new locations. He recalls the government's vow to rehabilitate slum areas by 2005; they failed miserably. Despite this, a few Dharavi dwellers are supportive of the special economic zone project, somehow believing that they will be among the tiny fraction of those who will receiving new housing.

Throughout the tour, I see factories dedicated to making soaps, snacks, pots, and clothing. Recycling is an important industry in Dharavi, so after garbage is sorted by ratpickers, plastic trash is sold here to be reprocessed. The money Dharavi residents spend on buying plastic garbage, they recoup by selling remanufactured plastic pellets. They also recycle tin cans and barrels, peeling off labels, heating them up, and banging them back into shape before reselling them to various companies. This "slum" is also where ALL Mumbai leather comes to be tanned.

The tour continued with a stop to the school funded by Reality Tours and Travels, where slum children learn English (Davindra tells me that Dharavi parents know how important education is, and push their kids to complete at least a basic education). It ended with his inviting me to his own home, which is in the pottery area of the slum, dominated by families that migrated from Gujarati a couple generations back. His home is neat and tidy (it's literally as big as a hallway), and his mother and sister are napping on the floor in the kitchen. The home has tiled floors, painted walls, electricity, a ceiling fan, a TV, and a refrigerator. It is undoubtedly super-cramped, but it's not a slum dwelling by any stretch.

I don't know what will happen to Dharavi...will the special economic zone pushers win? I'm very wary of "slum rehabilitation" projects. I can see why it's frustrating that Dharavi takes over prime real estate in a city like Bombay (where some apartments are more expensive, per square foot, than anywhere else in the world), but if public health was more of a priority, maybe the first low-income families would not have felt the need to settle here back in the 1860s, when Dharavi was nothing more than a landfill.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Today's headlines: How it is for the average poor female

I was bitterly surprised to read a quote by a famous Bollywood actor in the newspaper who claimed that the plethora of curvaceous female role models in the film industry is indicative of the improvement of women's status in Indian culture. Have they stepped out of their posh homes to see what the rest of India is like?

Thanks to my wandering through India this summer, I have. And women's status has indeed been improving in scattered areas as a result of the hard work of a few NGOs (I'm not going to get started on the ample corruption that clouds such efforts, just the ones that actually get something DONE for the target communities).

You don't have to travel three hours in a bumpy, overcrowded bus or tour destitute villages to get a taste of what it means to be a low-income female in this country. Just pick up the paper every day, and you'll soon find out.

Some of today's related news (I've been reading the paper for weeks now, this is typical):

-22-year old girl is harrassed for dowry and for bearing a female child, so she protests the mental and physical abuse she has suffered from her in-laws by walking around Gujarat in her underwear. Upon arriving at the police station, she tries to immolate herself as a demonstration but is restrained.

-2-day-old infant is found buried alive in Andhra Pradesh by her grandparents, because she is the seventh girl in the family.

-Due to unclear laws on the legal age of marriage for a girl in India, 15-year-old girls are being coerced into marriage. High Courts refuse to press rape charges, ruling that the 'age of discretion' has been reached at 15 years of age. No law fixing the uniform age for consensual sex exists.

-26-year-old girl working as a domestic help is brutally stabbed by her 22-year-old lover nine times with a pair of scissors, because she refused to continue the 'relationship' (the other day, a young, pregnant woman was bludgeoned to death by her lover as bystanders looked on, doing nothing. By the time someone finally put her into a rickshaw and sent her to the hospital, it was too late. She was killed for insisting that her lover marry her after discovering she was pregnant).

So no, famous Bollywood stars, things are not necessarily changing for the average poor woman in India, and they are certainly not changing because of how strong, sexy, rich and wholesome Bipasha Basu, Kareena Kapoor, Rani Mukherjee and Aishwarya Rai are.

Thanks to my wandering through India this summer, I have. And women's status has indeed been improving in scattered areas as a result of the hard work of a few NGOs (I'm not going to get started on the ample corruption that clouds such efforts, just the ones that actually get something DONE for the target communities).

You don't have to travel three hours in a bumpy, overcrowded bus or tour destitute villages to get a taste of what it means to be a low-income female in this country. Just pick up the paper every day, and you'll soon find out.

Some of today's related news (I've been reading the paper for weeks now, this is typical):

-22-year old girl is harrassed for dowry and for bearing a female child, so she protests the mental and physical abuse she has suffered from her in-laws by walking around Gujarat in her underwear. Upon arriving at the police station, she tries to immolate herself as a demonstration but is restrained.

-2-day-old infant is found buried alive in Andhra Pradesh by her grandparents, because she is the seventh girl in the family.

-Due to unclear laws on the legal age of marriage for a girl in India, 15-year-old girls are being coerced into marriage. High Courts refuse to press rape charges, ruling that the 'age of discretion' has been reached at 15 years of age. No law fixing the uniform age for consensual sex exists.

-26-year-old girl working as a domestic help is brutally stabbed by her 22-year-old lover nine times with a pair of scissors, because she refused to continue the 'relationship' (the other day, a young, pregnant woman was bludgeoned to death by her lover as bystanders looked on, doing nothing. By the time someone finally put her into a rickshaw and sent her to the hospital, it was too late. She was killed for insisting that her lover marry her after discovering she was pregnant).

So no, famous Bollywood stars, things are not necessarily changing for the average poor woman in India, and they are certainly not changing because of how strong, sexy, rich and wholesome Bipasha Basu, Kareena Kapoor, Rani Mukherjee and Aishwarya Rai are.

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

Anti-US Sentiments in the World's Most Populous Democracy

I haven't blogged for a few days as it hasn't been easy to relate shopping and bargaining and overeating to public health in any meaningful way (especially after the past month of hospitals, care homes and ARV clinics).

But I'm nothing if not resourceful, so I'm going to make a blog out of a Hindi film that just came out called Apne (Yours). It's about two sons who become champion Indian boxers and fight their way to the final round of the World Championships to face a killer opponent: Luca Gracia of the United States. (Luca is African-American, which seems to make him more menacing to Indian audiences)

The film is about more than boxing. It's even about more than family honor, which is all Indians need to get roped into a movie. It's about National Pride.

These Indian brothers, played by Sunny and Bobby Deol, didn't start out as boxing champs. Their father was a contender who was banned from the sport after doping charges were leveled against him. He wants to train his younger son, Bobby, to win the Asian championship and earn the privilege of fighting against Luca. When Bobby does face Luca, the U.S. athlete cheats to win, putting grease on his gloves and smearing them on Bobby's eyes (yes, Hindi movies are this dramatic...you don't know the half of it). In just 30 days, brother Bobby decides to train himself to face Luca...not just for family honor but, as I said, for the honor of the country.

Driving home this point about country honor was interesting to me. It's telling that the world champ Luca is from the U.S., and that he is portrayed as a killer opponent who cheats to win (and who has the goods to do it). Luca even tells the Indian trio (Sunny, Bobby and dad) that it doesn't matter who wins. It's not about honor, it's the money that matters.

Does this sound familiar? First of all, does this portrayal truly reflect Indian sentiment toward the U.S.? Is it just India, or South Asia in general? Is there any truth to it?

My opinion: yes, yes, and yes.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

It's all about small business

I just read in this morning's edition of The Times of India something that I've suspected for awhile: India doesn't support small business the way it should, and that fact is costly for individual and national economic welfare.

The World Bank produces rankings, judging countries by the amount governmental support is given to budding entrepreneurs. The US, a nation that has built up its economy largely on the success of small business, ranked third, after Singapore and New Zealand. Also in the top 5 are Canada and Hong Kong. India ranked 46th out of just 53 countries...China was not much better, placed at 42.

Surprised?

What is this ranking all about? Does it have anything to do with economic prowess? We are always talking about the two up-and-coming nations in Asia, China and India. How can these countries be so low on this indicator, lower on the list than Latvia, Peru and Uganda?

It's not that you don't find entrepreneurship in India. Lining every street are entrepreneurs, whether they're peddling chai, paan, AA batteries or dyed fabrics. The problem is that they are not given the financial support from the public sector to make their businesses grow. As a result, the lower-class shop/stall/booth-owner on the street is perenially unstable. Instead of moving up in life through his business, he continues to live with his family in a shack made of metal scraps, plastic sheeting and flattened cardboard boxes. He might sleep on the floor of his shop, and you'll have to wake him up in the morning if you want service. It's obvious that he isn't getting significant tax breaks, write-offs, or any other appreciable incentive to make his business (and his living standards) grow.

Why should the government care about this? Because it has no middle class whatsoever. As with everything else in this country, a multi-sectoral approach is desperately needed. If we touch one part of society/economics/politics without a comprehensive stakeholder analysis, it could have disastrous consequences. But what the World Bank rankings on country support for entrepreneurship tells me is that another element of socioeconomic well-being has been singled out, and that is small business.

Also on the news front in India: more rains, more hectares of land diverted for special economic zones (SEZs), more accidental deaths (boy falls in crack between escalator and railing; bus crashes into cars, killing child; 14 die in monsoon floods), more friction in the Gulf (although ideological brothers Iran and Venezuela are apparently cozying up over their common enemy, the US); and more attention sickeningly diverted from actual news to trashy news, all over the world (Bollywood takes precedence over public health, Paris Hilton replaces Michael Moore on Larry King Live...I think I can leave it at that).

Also interesting, but not directly related to India, is Iran's new position on rationing petrol, and the ensuing riots at gas stations. Citizens were shocked by the announcement that petrol would suddenly now be rationed before anyone, even the rich, could stock up. We fight over nuclear weapons that may or may not exist (does it even matter, given our current world issues???). I cannot imagine what chaos will ensue when we start to fight over fuel. Eventually, some good will come from it, including more rapid conversion to biofuel and other eco-friendly energy alternatives.

The World Bank produces rankings, judging countries by the amount governmental support is given to budding entrepreneurs. The US, a nation that has built up its economy largely on the success of small business, ranked third, after Singapore and New Zealand. Also in the top 5 are Canada and Hong Kong. India ranked 46th out of just 53 countries...China was not much better, placed at 42.

Surprised?

What is this ranking all about? Does it have anything to do with economic prowess? We are always talking about the two up-and-coming nations in Asia, China and India. How can these countries be so low on this indicator, lower on the list than Latvia, Peru and Uganda?

It's not that you don't find entrepreneurship in India. Lining every street are entrepreneurs, whether they're peddling chai, paan, AA batteries or dyed fabrics. The problem is that they are not given the financial support from the public sector to make their businesses grow. As a result, the lower-class shop/stall/booth-owner on the street is perenially unstable. Instead of moving up in life through his business, he continues to live with his family in a shack made of metal scraps, plastic sheeting and flattened cardboard boxes. He might sleep on the floor of his shop, and you'll have to wake him up in the morning if you want service. It's obvious that he isn't getting significant tax breaks, write-offs, or any other appreciable incentive to make his business (and his living standards) grow.

Why should the government care about this? Because it has no middle class whatsoever. As with everything else in this country, a multi-sectoral approach is desperately needed. If we touch one part of society/economics/politics without a comprehensive stakeholder analysis, it could have disastrous consequences. But what the World Bank rankings on country support for entrepreneurship tells me is that another element of socioeconomic well-being has been singled out, and that is small business.

Also on the news front in India: more rains, more hectares of land diverted for special economic zones (SEZs), more accidental deaths (boy falls in crack between escalator and railing; bus crashes into cars, killing child; 14 die in monsoon floods), more friction in the Gulf (although ideological brothers Iran and Venezuela are apparently cozying up over their common enemy, the US); and more attention sickeningly diverted from actual news to trashy news, all over the world (Bollywood takes precedence over public health, Paris Hilton replaces Michael Moore on Larry King Live...I think I can leave it at that).

Also interesting, but not directly related to India, is Iran's new position on rationing petrol, and the ensuing riots at gas stations. Citizens were shocked by the announcement that petrol would suddenly now be rationed before anyone, even the rich, could stock up. We fight over nuclear weapons that may or may not exist (does it even matter, given our current world issues???). I cannot imagine what chaos will ensue when we start to fight over fuel. Eventually, some good will come from it, including more rapid conversion to biofuel and other eco-friendly energy alternatives.

More on Mumbai

Yesterday's post on my first impressions of Mumbai was just that-the first impressions. Today I got a better taste of what this city is all about, and I have some more to say.

As an aside, I have to admit that in order to interest you I've had to get more creative with these posts as I'm no longer visiting care homes and hospitals and interacting with interesting people in the field. So now I'm just touring cities and talking about whatever comes to mind.

Anyway, today Sej and I were very lucky to have our very own tour guide, Kiran. Kiran is a family friend of Renu Aunty (a family friend of my parents), with whom we are staying while we're here in Mumbai. Kiran showed us the major universities of Mumbai, including St. Xavier's, Bombay University, and Jai Hind College. It was interesting to see how different they all are.

We also got to see some of the architecture typical of the city. It is distinctly different from any other city I've seen in India (and by now I feel like I've seen many). It's heavily influenced by the British. Train stations look like churches, with tall steeples and intricacies that you'd never expect from a simple public transportation building. The buildings are very very old, but surprisingly still standing despite 150 years (give or take) of wear and tear. Not all the buildings are old; there are so many high rises being built in the city, too. From apartments to corporate offices, Mumbai's skyline is rapidly growing. The mix of old and new buildings is interesting to see...more of that contrast/disparity we always talk about.

To get around, we relied on public transportation, which was an experience in itself (especially in the pouring rain!). We took the bus to the center of town, and a train to get back home (we live in a residential area of Mumbai). The bus was very convenient, and since it's Sunday, we didn't have to deal with the usual full frontal assault that is an Indian bus ride (Kiran agrees...she says that you come out of the bus half-raped, usually). The state of the trains is really bad, but it's so convenient that what it lacks in beauty, it makes up for (somewhat) in usability. However, Kiran told us that she's seen dead bodies on the train, because they are so packed during the weekdays that there isn't enough room for all the riders. They fall off the train onto the tracks. Another public health concern in a country that has more than its share.

Another interesting thing we did today was to go to Mocha, a hip coffee shop and hookah bar where teenagers and college students seem to pass their time smoking, flirting, and seeing and being seen. It was interesting to see young Indians being more "American" than me, smoking hookah, wearing lots of makeup, being totally comfortable with public displays of affection, etc. It was also a public health concern, as people were smoking indoors and we had to sit there and endure it. But that's a giant of an adversary here in India, tackling smoking in public places.

Lastly, this morning I finally went to the park to go jogging! It wasn't raining (it started pouring literally minutes after I arrived home), so I spent a good 45 minutes there. It was a Sunday morning...everyone in town that was up seemed to be there. Kids played cricket and soccer, ignoring the muddy puddles everywhere (or, more accurately, reveling in them). The elderly gathered around in the middle of the track to read the paper. Women power-walked in groups. Men strolled with their dogs...on LEASHES. It made such a difference to my impression of the city, to see everyone congregating in such a healthy way. What a huge public health blessing a decent, centrally located park is!

In the evening, we sat around munching snacks and talking about everything from life in the Gulf Coast (Kiran's family spent a lot of time there) to fashion in India and politics in the US. Life in Dubai is apparently very different from what you would expect in a Muslim country, with gay bars, excessive drinking (and driving), and ladies nights out. British immigrants apparently treat Dubai Indians like their servants, thinking they are superior simply because of their British passports. Kuwait is very shallow, with dinner conversations centered around people's income. The US media is deplorable. Mumbai real estate (in certain areas) is among the most expensive in the world. It was interesting to talk about all of these things, because in some way or another, they all affect my favorite topic: public health.

Saturday, June 30, 2007

First impressions of Mumbai

So it's my first full day in Mumbai, and after driving around the city, I've had some time to form a few (public health-related) impressions.

The monsoon season hits Mumbai hard, which brings a host of issues in itself. The air is so humid and thick you can take a shower three times a day and still feel sticky. The weather is a breeding ground for water-borne diseases like malaria and yellow fever. Already, there have been reports of an unusually high number of malaria cases in the area...and that was before the monsoons even arrived this summer.

The rains bring more than infectious disease, although that in itself is disastrous to many people, particularly those living in the slums (Mumbai is home to the largest slum area in Asia, Dharavi). It also rips up the roads, creating huge craters that rickshaws and cars get stuck in, clogging the roads and endangering the lives of both drivers and pedestrians.

I've written about sanitation problems before, but multiply those at least twofold for a city like Mumbai, because of the rainy season. City planning is very poor, and the rains create terrible sanitation issues. Aside from the standing water everywhere, there is so much trash all over the streets. Scraps of food, rotting carcasses, plastic waste...these are all the types of things you'll encounter while walking (in your sandals!) on the road. It is deeply, deeply unsanitary.

Then there's the beaches. People visit the water in Mumbai for both religious and recreational purposes. There is the festival of Ganpati, where figures of the elephant god are made out of plaster of paris and then dunked into the water. There's Juhu Beach, which is famous for its beachside fun and its chaats (spicy snacks). Today, we had tea by the beach and until we walked closer to the waves, we didn't realize that the sand was chock full of all kinds of TRASH. How can beach goers bathe safely among so much trash? In Los Angeles, studies are done to estimate the social and economic costs of dirty beaches. It is SO much worse here in Mumbai.

Something must be done to improve the cities of India. Proper drainage must be installed; the rains will continue here from July until September. People are unable to go to work; many trains are not functioning and people are wary to step out of their houses after the flooding and loss of lives two years ago. The government has made no improvements to thwart another similar disaster. So much productivity is lost, meanwhile, in a country that cannot afford to lose productivity!

What can be done about the trash? What can be done to instill in Indian citizens a sense of civic duty? What can be done to inspire the government to make city planning a priority? To fix the roads so that huge craters don't punctuate the streets?

The monsoon season hits Mumbai hard, which brings a host of issues in itself. The air is so humid and thick you can take a shower three times a day and still feel sticky. The weather is a breeding ground for water-borne diseases like malaria and yellow fever. Already, there have been reports of an unusually high number of malaria cases in the area...and that was before the monsoons even arrived this summer.

The rains bring more than infectious disease, although that in itself is disastrous to many people, particularly those living in the slums (Mumbai is home to the largest slum area in Asia, Dharavi). It also rips up the roads, creating huge craters that rickshaws and cars get stuck in, clogging the roads and endangering the lives of both drivers and pedestrians.

I've written about sanitation problems before, but multiply those at least twofold for a city like Mumbai, because of the rainy season. City planning is very poor, and the rains create terrible sanitation issues. Aside from the standing water everywhere, there is so much trash all over the streets. Scraps of food, rotting carcasses, plastic waste...these are all the types of things you'll encounter while walking (in your sandals!) on the road. It is deeply, deeply unsanitary.

Then there's the beaches. People visit the water in Mumbai for both religious and recreational purposes. There is the festival of Ganpati, where figures of the elephant god are made out of plaster of paris and then dunked into the water. There's Juhu Beach, which is famous for its beachside fun and its chaats (spicy snacks). Today, we had tea by the beach and until we walked closer to the waves, we didn't realize that the sand was chock full of all kinds of TRASH. How can beach goers bathe safely among so much trash? In Los Angeles, studies are done to estimate the social and economic costs of dirty beaches. It is SO much worse here in Mumbai.

Something must be done to improve the cities of India. Proper drainage must be installed; the rains will continue here from July until September. People are unable to go to work; many trains are not functioning and people are wary to step out of their houses after the flooding and loss of lives two years ago. The government has made no improvements to thwart another similar disaster. So much productivity is lost, meanwhile, in a country that cannot afford to lose productivity!

What can be done about the trash? What can be done to instill in Indian citizens a sense of civic duty? What can be done to inspire the government to make city planning a priority? To fix the roads so that huge craters don't punctuate the streets?

Friday, June 29, 2007

HAPPY BIRTHDAY NEENER!!!

Today is my sister Neener's birthday (you might know her as Reshma but inexplicably she's become Neener to me). Reshma means a thread of silk in Hindi. My sister is beautiful inside and out-if you know her you can vouch for that-but she's anything but soft and delicate, if you ask me. In my world, that's a high compliment.

Life is not about being soft and delicate...at least not most of the time (although it depends which path you take in life). I have no brothers, so my sister and I grew up not really knowing what it means to be a girl. We grew up thinking we were the same as boys. Of course, that's not exactly true. But my sister's fight and passion in life have always inspired me. Those qualities are especially useful here in India, where among one billion people, you have to be loud sometimes to get your voice heard (whether what you want is a cup of chai, or funding from an NGO for second-line ARVs).

My sister has lofty goals on the global business front, but the funny thing is that they are only lofty if you don't know her. If you do, you realize that her determination to harness market forces to solve global health problems is just about par for the course. She's already on her way there, with a prestigious internship at Gilead, a corporation known for its poverty-fighting activities in developing countries. She's also co-leading a team of fellow Stanford MBA students on an exchange program at the internationally renowned Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore.

With such an impressive resume building up, you'd think my sis would be getting a big head about it. That couldn't be further from the truth (she doesn't need fancy accolades for that! just kidding!!!) The truth is, she picked Stanford because of its commitment to fighting poverty with business acumen, and joined Gilead for similar reasons. God has blessed her with immense talent (plus, more importantly, she's the funniest person I know), so I really lucked out to get her for my big sis. Happy birthday Neener! You're good for the future of global public health.

One of my favorite Neener-inspired ideas: "The closest way to a public health solution is through business." Remember me when you're famous! And when you shop.

Life is not about being soft and delicate...at least not most of the time (although it depends which path you take in life). I have no brothers, so my sister and I grew up not really knowing what it means to be a girl. We grew up thinking we were the same as boys. Of course, that's not exactly true. But my sister's fight and passion in life have always inspired me. Those qualities are especially useful here in India, where among one billion people, you have to be loud sometimes to get your voice heard (whether what you want is a cup of chai, or funding from an NGO for second-line ARVs).

My sister has lofty goals on the global business front, but the funny thing is that they are only lofty if you don't know her. If you do, you realize that her determination to harness market forces to solve global health problems is just about par for the course. She's already on her way there, with a prestigious internship at Gilead, a corporation known for its poverty-fighting activities in developing countries. She's also co-leading a team of fellow Stanford MBA students on an exchange program at the internationally renowned Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore.

With such an impressive resume building up, you'd think my sis would be getting a big head about it. That couldn't be further from the truth (she doesn't need fancy accolades for that! just kidding!!!) The truth is, she picked Stanford because of its commitment to fighting poverty with business acumen, and joined Gilead for similar reasons. God has blessed her with immense talent (plus, more importantly, she's the funniest person I know), so I really lucked out to get her for my big sis. Happy birthday Neener! You're good for the future of global public health.

One of my favorite Neener-inspired ideas: "The closest way to a public health solution is through business." Remember me when you're famous! And when you shop.

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

It's not easy being green

In California, it's hip to talk about clean fuel and recycling. Driving a Prius is "in". People who litter can expect dirty looks along with steep fines. We're all about the environment.

Given that I've lived my whole life in such a setting, I did not expect to come to India and feel like this country is a step ahead of the US in terms of converting to eco-friendly fuel. Almost all buses, and many other vehicles, sport the CNG logo, indicating that they run on certified natural gas. As I mentioned on my entry a couple weeks ago on Sawai Madhopur (tiger land), many village homes get their fule from biodigesters and similar methods-much more environmentally sound than what we have in the US. Remember how the Prakratik Society urges villagers to plant trees to offset wood-burning? Do we have that kind of accountability? What's the deal?

The deal is, environmentally, India might actually have an advantage over the US and countries like it. It's easier to go from having no buses at all (in some areas of India) to CNG buses. It's way more efficient to install biodigesters in villages that had not previous power source, rather than tear up old infrastructure and install new, incompatible systems.

So in the developed countries, or at least in most parts of them, our modern way of thinking-green is cool-still needs to be translated into action. Fewer SUVs. More public transportation. Cleaner burning fuel and more hybrid vehicles. More planting of trees and smaller carbon footprints for each transnational corporation, factory, family, and individual.

It's a tall order. Buses crammed with 100+ people may fly here in India, but people in the US don't want to deal with public transportation if they can afford not to (and most can). It's tough to go backwards, socioeconomically, once you've had the luxury of your own personal vehicle (and a sports utility one at that), your own power source, your own unlimited resources so long as you can foot the bill.

Not that India doesn't have its own hands full, environment wise. Pollution here is horrible. The rising middle class is suddenly able to afford cars, which is reflected in increased smog, toxic air (and rampant respiratory diseases), and unfailingly clogged, chaotic roads. But all I'm saying is that India is taking practical steps forward. Maybe it's not enough, maybe it's just a drop in the ocean, but it's a tangible effort.

Developed countries may be able to get away with doing nothing. They have lower population sizes, the ability to afford carbon credits, if they are ever implemented, and the ability to pay for skyrocketing fuel prices. It's even been said that global warming won't hit the richer countries so hard as the poor ones. Even if countries start to convert to biofuel, poor countries will face disadvantages because precious land (thousands and thousands of hectares in one state of India alone, as specified by Indian Oil) will be converted from food crop use to fuel crop use. Creative solutions, like using only crops that can be used for both food and fuel (ie corn, sugar cane) may need to be implemented. Even more complex is the fact that crop prices have already started to rise in response to the growing demand for biofuel raw materials. This will have negative consequences in countries dealing with suffering subsistence farmers and rising national food insecurity.

Given that I've lived my whole life in such a setting, I did not expect to come to India and feel like this country is a step ahead of the US in terms of converting to eco-friendly fuel. Almost all buses, and many other vehicles, sport the CNG logo, indicating that they run on certified natural gas. As I mentioned on my entry a couple weeks ago on Sawai Madhopur (tiger land), many village homes get their fule from biodigesters and similar methods-much more environmentally sound than what we have in the US. Remember how the Prakratik Society urges villagers to plant trees to offset wood-burning? Do we have that kind of accountability? What's the deal?

The deal is, environmentally, India might actually have an advantage over the US and countries like it. It's easier to go from having no buses at all (in some areas of India) to CNG buses. It's way more efficient to install biodigesters in villages that had not previous power source, rather than tear up old infrastructure and install new, incompatible systems.

So in the developed countries, or at least in most parts of them, our modern way of thinking-green is cool-still needs to be translated into action. Fewer SUVs. More public transportation. Cleaner burning fuel and more hybrid vehicles. More planting of trees and smaller carbon footprints for each transnational corporation, factory, family, and individual.

It's a tall order. Buses crammed with 100+ people may fly here in India, but people in the US don't want to deal with public transportation if they can afford not to (and most can). It's tough to go backwards, socioeconomically, once you've had the luxury of your own personal vehicle (and a sports utility one at that), your own power source, your own unlimited resources so long as you can foot the bill.

Not that India doesn't have its own hands full, environment wise. Pollution here is horrible. The rising middle class is suddenly able to afford cars, which is reflected in increased smog, toxic air (and rampant respiratory diseases), and unfailingly clogged, chaotic roads. But all I'm saying is that India is taking practical steps forward. Maybe it's not enough, maybe it's just a drop in the ocean, but it's a tangible effort.

Developed countries may be able to get away with doing nothing. They have lower population sizes, the ability to afford carbon credits, if they are ever implemented, and the ability to pay for skyrocketing fuel prices. It's even been said that global warming won't hit the richer countries so hard as the poor ones. Even if countries start to convert to biofuel, poor countries will face disadvantages because precious land (thousands and thousands of hectares in one state of India alone, as specified by Indian Oil) will be converted from food crop use to fuel crop use. Creative solutions, like using only crops that can be used for both food and fuel (ie corn, sugar cane) may need to be implemented. Even more complex is the fact that crop prices have already started to rise in response to the growing demand for biofuel raw materials. This will have negative consequences in countries dealing with suffering subsistence farmers and rising national food insecurity.

Sahastradhara and School-Based HIV/AIDS Education in Uttaranchal

From Ajay's travel blog...pretty similar to my own, except my pictures have about 3x more people!

Yesterday was another interesting day in Dehradun. Waking up for our last full day here, we thought we'd make a lazy day out of an internet cafe session, coffee shop relaxing, and other in-town pursuits.

Of course, that's not what happened. We did do all of the above, but we also made an impromptu trek to Sahastradhara, a cool sulfur spring embedded in the mountains. We had no idea what to expect, really, but in my mind I pictured a series of clear, deserted pools emitting a faint scent of boiled eggs.

Sahastradhara is neither clear nor deserted (come on, this is India), and the smells are of sweaty people, not sulfur. The pools themselves are undeniably beautiful (though probably not their natural color anymore), situated among mountain ranges and punctuated by big boulders. They ARE arranged in series, like a waterfall. But like Mussoorie, Sahastradhara has become a crazy tourist attraction full of food stalls and souvenir shops, trash, and PEOPLE.

The best part of our trip was the ride up the mountain. We took a bus, which, if you've never been in one, is quite an experience in Idnai. I got to know a LOT of people in that bus, if you know what I mean. You get stepped on, sat on, rubbed up against...ahhh, there's nothing like it. The views, as always, were gorgeous. Nature never disappoints; we humans are what deface things.

To treat ourselvse for finishing the last tourist attraction in Dehradun, Sej and I went to the haven that is McDonald's and got well-deserved junk food. It felt like imminent rain, so it was hot and humid as we walked the long walk back from the bus depot to our section of Rajpur Road (where we're staying). As soon as we got back, it started pouring. It's still coming down strong today. Monsoon season!

Now for the public health related part. Dehradun is located in Uttaranchal, and happens to be home to one of the two most prestigious prep schools in India. However, the fledgling state of Uttaranchal has just definitively banned school-based HIV/AIDS education because of traditionalist thinkers who fear talking about HIV in schools will encourage earlier sexual behavior among children.

Ironically, this is the same state that's pushing for IT and e-literacy for all in the next few years. What do you think children do on the internet? Not everyone looks up gossip and sports. I can tell you from my time spent in cyber cafes (where cookies are unfortunately not always cleared after use) that sex education is definitely taking place on the internet.

The UN has declared that school-based sex education actually deters early sexual behavior among youth; why, then, is India (and the world) having such a hard time with it?

As usual we are, foremost, victims of ourselves.

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

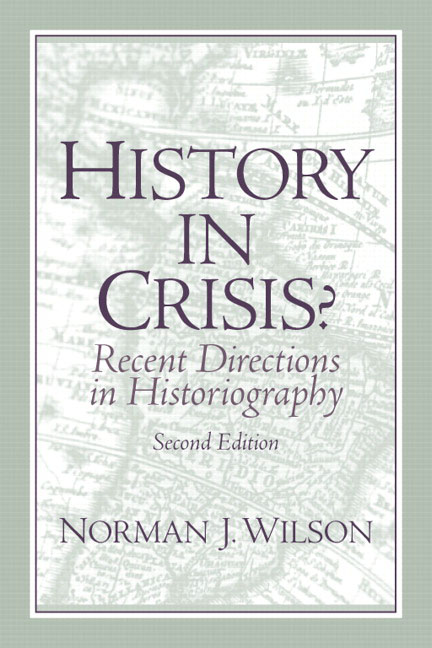

Historiography and Public Health

There are only a few voices in history, and they are the rich ones.

As a comparative literature major in college, I am most intrigued by the concept of history as works of literary fiction. I specialized in Latin American literature, and found that throughout various important literary time periods, colonial history-a history of occidental subjugation and exploitation-is deeply embedded in literary works (both colonial and postcolonial/postmodern). As a result, Latin American fiction is anything but. It’s a politically charged, militant vehicle to say what, in the real world, cannot be said. Meanwhile, history books written by conquerors sing their one-sided tune, painting a picture on the surface of things while destroying native culture and truth on the side. This is not history. This is historiography-the crafting of stories.

So what does this mean for India? There is a point. India is another country that not so long ago was under imperialist rule. After gaining its independence in 1952, the fledgling democracy suffered a lot of civil strife and poverty. Freedom has its costs, whether the emancipated party is Black slaves in America, Latin American countries under USSR/US occupation, or Indians ruled by the British. In Bharat’s case, Muslim-Hindu tension heightened, Pakistan was born, and population-and its partner in crime, poverty-exploded. Public health, as usual, suffered dearly.

Muslim-Hindu tensions are still high. The most ornate Hindu temples in Delhi (such as Akshardham) are high on the supposed Islamic terrorist list (according to Sej, my Hindu culture informant). It’s still considered controversial for Hindus and Muslims to marry-better a Hindu marry a Christian or a Sikh than a Muslim! I feel the tension myself when Hindus talk about the introduction of Islam to India-it is always portrayed as a shameless invasion by Moghuls who forcefully converted their subjects to the austere religion.

However, I just read an article in the Times of India that argues that the Moghul invasion theory is a myth, not a fact. The scholastically accepted version of history is now that Arab traders brought Islam into the country-not by force, but peacefully.

So, my faithful readers (hi Mom, Dad, Neener and Grandma) that I’m Muslim. But I’m not trying to defend my religion at all-it makes no difference to my identity or my faith how Islam came to influence my mother country. I AM, however, interested in this bit of history from a public health perspective. It’s not just Muslim-Hindu conflict that affects Indian public health, but tribalism and religious/ethnic clashes in general. Sometimes, individual pride, mistrust, and hatred of the Other run so deep that castes and tribes don’t even stop to think that their inability to unite under common causes (education, health, electricity, sanitation, city planning) results in much more damage to their communities than anything else.

Of course, from a social-ecological perspective, these individualists are not to blame; it’s not their fault. There are always deeply embedded root causes that explain surface tension. India’s immature democracy has the gargantuan task now of building political parties capable of appealing to hundreds of scheduled tribes (as well as the growing, modern middle class). I think the answer lies in human development-not just empty campaign promises during election months, but real follow through in areas of public health. That’s a cause no ethnic group should reject, if communication is effectively executed by the public sector (if only…).

Mussoorie Day Trip - A Hill Station in the Himalayas

Sej is featured in several of my photos. She has all of my pictures and I have all of hers. We've become very efficient at alternately running in front of a scene to have our pictures taken by each other!

Kempty Falls...ok, it's not Niagara, but it's a natural waterfall! I ain't complaining.

Today we went to Mussoorie, the main attraction of Dehradun. The Himalayas are breathtaking, although the little town was way too populated to take in the beauty of the mountains themselves. But still, it was amazing. When you stand in a mountain range like this one, you start to feel how small you are, and how you're just a part of something bigger and very, very amazing. Praise God.

Another interesting thing about Mussoorie is how much British influence is reflected in the architecture. As Sej pointed out, a lot of the buildings (and the windows, specifically) are not Indian. There are a lot of old structures, too--the library is dated to 1843. This was a British settlement. It makes me angry when I think about how imperialists claimed this beautiful mountain area as their own, making ugly pink buildings and bringing plastic and other types of garbage here. It's the Himalayas!!! It's a town among the clouds. And now it's way too touristy. In my opinion (and I probably am in the minority here), the ride up to and down from Mussoorie is much more calm and engaging than the town itself.

Monday, June 25, 2007

Bollywood and HIV/AIDS in India

The first photo is of Kareena Kapoor, who never disappoints by wearing too much clothing. The second is one of Shah Rukh Khan's scenes in the movie Sheesha. The first is from imageshack.com, second from timesofindia.com (click for source).

Having just watched my first blockbuster Bollywood film in India in a long time, I am shocked by just how much Indian pop culture has changed...for the worse. The cheapness of it is disheartening. Now, I'm definitely an old fashioned girl in this modern world, in some ways--in my world view there's no drunken partying, sleeping around, cleavage displays/miniskirts, and potty mouths (though I can be a brat sometimes, but that's different). But by any measure, Bollywood has definitely gotten more...modern in the past few years. Before, the scant clothing was there, but stars wouldn't openly kiss onscreen, and sex scenes (except the most subtle hint of them) were nonexistent. Suggestions of premarital sex were depicted as rare and negative (prostitutes, corrupt men, etc). This has changed. Films like Salaam, Namaste and Jhoom Barabar Jhoom reflect the changing values of this lumbering, developing country. Along with the high tech cell phones, latest fashions, and glossy scenes, tv and film depict India's anti-traditional cultural development (to be distinguished from what concerns public health--and me--that is, human development). India is inching further away from being that nation rich with history, culture and diversity; it's getting closer and closer to a modern democracy driven primarily by market forces. It's not as far along on that pathway as some other countries (eg, China), and its great diversity and population size will slow it down considerably, but I've noticed a definite shift in popular values.

What's the result? I just spent a day with my distant cousin Kirtina. She's 12 years old, lives in an upper middle class apartment complex in a very nice part of Delhi, and is fascinated by both US and Indian pop culture (these days, what's the difference--if anything, the Indian version is even more "pop" than its US counterpart). She loves The Disney Channel, Nickelodeon, and Hindi serials and films like Jhoom. She is seduced by the song, dance and drama of the media--the same media that allows superstars to smoke onscreen, depict premarital relationships as the new norm, and wear clothing that leaves nothing to the imagination.

If public health efforts in India don't keep up with the "westernization" of Indian pop, STDs (and particularly HIV) could become an even bigger issue in the country than it already is. Effective prevention campaigns, school based awareness and family involvement are all needed to catch up with the poorly regulated media circulating in India today. The anomaly is that despite the fact that pop culture has become so lax and open, society still clings to traditional beliefs that sex should not be openly discussed (particularly with kids). Parents and teachers, astonishingly, don't want school based sex education, nor do they take it upon themselves to educate their children at home. There's the rub.

The solution? That's a tough one. Perhaps it would help to recruit age appropriate superstars to speak up for the cause. Since parents need to get on board, an older film/tv star would help to convince them. Kids would likely respond to younger stars, obviously--and not just Hindi stars, but American ones too. Lizzie Maguire, That's So Raven, and the newest Nickelodeon shows are all really big here. HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention messages can be incorporated into story lines, too, the way they are in the US. Of course, ignoring the issue is a convenient and attractive option. But not dealing with it is one way to predict that it'll haunt Indian public health for decades to come.

Mewat in Pictures

The younger students. The one on the left was the Twinkle Twinkle Little Star fan. The one on the right was the littlest student, and kept unwittingly torturing this newborn kitten, which elicited some muted admonishing from me.

Group picture. We are in the way back...it was just me and Paulie, since Sej didn't feel well and Emma was tired from her trip to the Taj Mahal the day before.

The embroidery class. After looking at several designs I felt confident these girls' work can do well in the Delhi markets.

SPYM handprint mural outside the SPYM field office in Mewat. I hope to visit this village again soon! As Shalini said, there's something about working with these small, thin, raggedy, exuberant kids that makes it better than anything else. I felt this way at the St. Stephens' Outreach Center in Nandnargh (Delhi slum) too. Field work is where it's at.

Sunday, June 24, 2007

Mewat Trip!

Our last day of the program, we finally went to the village of Mewat in Haryana. It's one of the most backwards areas of the north, with extremely poor "health indicators" (a term created by developed nations). High infant and maternal mortality rates, low female literacy rates and poor sanitation are all part of life in Mewat. Malnutrition. Multiple children. Tribalism.

The trip there was an experience in itself. The roads were terrible, with big potholes and lots of digressions and dead ends. We had a very difficult time finding our way. There was also a lot of construction going on. We saw big tractors moving dirt, and half-built temples along the way. We also saw a few rickshaws crammed with at least 12 people in each...Indians piled upon Indians. That would never happen in America...we're too big and tall to fit that many people (heck, half that many people) in a little rickshaw!

Once we finally arrived at the SPYM office in Mewat, we immediately left for our first site visit to the school that the NGO has built up. SPYM has taken government funding and formed a public-NGO partnership to establish 20 schools in the village. There are public and private schools nearby, but so many children (age 4-15) lack basic education and cannot enter those schools without first having basic reading and writing skills...which SPYM is trying to impart.

There ar etwo groups of children in the school we visited, which is conveniently located in a residential part of the village among simple adobe houses, dirt roads, and heaps of cow dung. The first group we met was younger children (age 4-11). They don't know their alphabets yet, but the hope is that they will learn here and then transfer to public school (government fees are nominal...5-6 rs).

The educator and SPYM officer told us how difficult starting this project was. Money is not the issue...SPYM services are free, and government fees are so low. Here in Mewat, families don't see the point of educating their kids. They should instead stay at home and look after the smaller children (even a 4 year old is usually an elder sibling in these baby factory families). They think school (even just a few hours of it) is a waste of time. What would they do if not in school, besides tending to their siblings? Play with friends in the dirt, do menial chores, etc. It took a lot of convincing to get parents to send their kids to school. There were about 30 little ones in the "classroom" (an outdoor hallway with all the rugged kids sitting in rows on tattered pieces of cloth). SPYM has ben doing outreach for 15 years in Mewat, and I got the sense that a lot of knocking on doors, rapport building, and gaining trust had to be done for these children to be sitting there ready to learn. Shalini (CFHI program coordinator and SPYM health worker) encouraged us to play a game with the little ones, so we sang Twinkle Twinkle Little Star (we even got an encore request) and also played a version of Simon Says that we dubbed "Didi Bolo" (Sister Says). It was fun...kinda like being in kindergarten again.

After saying goodbye to the younger batch, who went home (a 1-minute walk at most) for lunch, we moved on to the second classrom, which was basically the floor space behind the first class. Here, another 20 or so older girls were huddled together (age 11-15). All had their hair covered by their dupattas, indicating that they are Muslims (the younger kids were a mixed group). Mewat is primarily Hindu tribes; Muslims are in the minority (it's that way in the vast majority of India). We were told that it was even harder to convince these girls' families to let their kids come to school for a few hours each day, because they are Islamic. Girls from these families are expected to marry soon, so why waste an education on them? SPYM convinced families of the usefulness of schooling by setting classes up as "cutting and sewing" instruction. Muslim families in Mewat were much more responsive to their girls' learning a marketable skill than the alphabet. However, on the side of cutting and sewing, SPYM teachers ensure that literacy instruction is given to the girls. It was shocking for me to see (of course, intellectually, I already knew from MPH classes) the effects of Muslim traditionalism on women's and family health. How could these women progress if their only expectation in life is to bear (male) children, cook food, serve chai, do farm work and iron clothes? How can they educate their kids if, from the time they are young, they are not even allowed to leave the house?

After the customary intro session of singing (you won't believe it, but I sang "Lean on Me"...solo...upon request for an English song, and one of the Muslim students sang a Hindi song in response), we got to interact with these girls who were so eager and open.

The student who sang, a slim, fair girl wearing a simple salwar and a white eyelet dupatta over her head, broke the ice by asking us what we thought of them. I was taken aback by the question...how to answer? There are so many first impressions. Lovely. Dirty. Ignorant. Bright.

What we DID say was that what they were doing in school is very important, and that it's a very good thing. Just think what they could have done if they'd had proper education earlier on? This is a big step forward they've taken in life, and they should be congratulated. Acchi baat hai (It's a good thing). They seemed to like this reaction, and it was 100% true.

We asked them what THEY thought of US. They wanted to know why on earth we had troubled ourselves to come all the way there to see them. Where did we come from? What were our names? They were very surprised to learn I'm Hindustani (do I not look Indian????). We asked whether any of them would continue their education in official school after this course. Several wanted to, but expressed their desire, I thought, tentatively. They had to convince their parents to let them come this far (to cut and sew, not to read and write), and might not succeed in making it much further before their parents arranged their marriages and they moved into their in-laws' homes.

After a photo session with the whole group (minus the little ones, who had retired for the day), we left the girls and teachers, and moved on to the next part of our trip, to SPYM's income generation and microfinance projects. First, we met with some younger girls (about 10 years old on average) who were practicing their embroidering skills. Their designs were actually beautiful, and the future plan is to have companies deliver plain salwar suits and other items so that these kids can embroider them for rs 40-50 ($1 US) each day. The goal is to get more money into the hands of women and girls--female empowerment en route to community health and well-being. These girls were bright and friendly, less quiet and mor eopen than the Muslim girls at the school (these girls were mixed, mostly Hindi and a few Muslims). They asked our names (and remembered them!) and told us theirs. They even taught us how to embroider!

Next, after a spicy cup of chai, we met with the microfinance group members. All are daughter-in-laws living in the village of Mewat. There are 17 members. In order to join, they must be daughter-in-laws, must own land (for collateral) and must have about 50 rs. per month to contribute to their joint bank account (they scrape this money together from household money given to them by their husbands). With all this money in the bank, they're able to take out loans to run small businesses for income generation.

It was interesting to talk to these women and see how they struggle to empower themselves. They initially had 20 members, but 3 dropped out because they didn't have faith in the project (and 50 rs. per month is a tall order in these parts of India). When they get the loan money, they give priority to the women who need it most, in a true co-op fashion. They give loans not just for business reasons but for household needs, too, such as dowry.

The microfinance ladies also chatted to us about the government's education and health care efforts. They expressed a lot of distrust in the public sector. They complained about government hospitals and schools; the MBBS's (MD's) in government hospitals are not trustworthy because there's so much corruption these days you can pay for an MBBS certificate, they said. Government schools are so bad the kids just play cricket the whole day. The women prefer taking their health care from private doctors ,whether their credentials are rael or not. One woman told us that if the treatments given by private practitioners work, and those given by MBBS's from big hospitals do not, she will choose the private "professional" as her usual source of care.

I can't help thinking of all the times in India we hear about or meet HIV cases where "quack" doctors and private clinics were involved in transmitting the disease (unscreened blood transfusions, re-used needles).

Shalini also told us something quite interesting: people here (and in fact, everywhere) mistrust anything that's free, be it chocolate or education or health care. If the same thing is offered by one person free, and by another person for a fee, they will go to the seller to pay, because they are convinced that the seller's product must be of higher quality (simply because it's not free). How to get around that one?? But the mistrust of government services is not only because they are largely free. Shalini said that despite these villagers' illogical mistrust of free services, government schools and hospitals do indeed provide low-quality care in many cases. It is never simple.

So...that was our day, in a nutshell. It was one of my favorite, if not my most favorite, CFHI India experiences. Even the part where I publicly humiliated myself by singing (but it was so graciously received and fervently translated by the illustrious Shalini). Meeting the Muslim girls made me think a lot about myself and my own beliefs. I'm Muslim too, yet the culture and treatment of women these Mewat Muslims subsribe to is alien to me. The positive thing is that SPYM is working to change things and is finding willing, wanting students.