I've been back from India for only a week, and I've already been back in an airplane twice. But Orange County, CA and Tucson, AZ are hardly as exhilarating as where I've been the past two months.

This is the life I've lived for 24 years: wide freeways, big cars, three-story houses, discount warehouses, central air conditioning, multiple cars, pressurized tap water, expensive pet food and services, excellent customer service, and so on. This is the life I'm used to...it's perfectly normal for me. Yet, as usual after a trip to a developing area, I feel very cynical about my surroundings and myself.

How much plastic waste do I generate shopping at Trader Joe's (as much as I adore it)? How much water do I waste when I make use of the wonderful, hot water that bursts out of the tap? How much extra food do I eat out of boredom? How much energy do I waste running on a belt at the gym for 45 minutes, spending so many calories but accomplishing nothing, for no one? How much gas do I waste satisfying my every whim and fancy, traveling wherever I want to go all by myself in my very own gas-guzzling car?

Ouch. I probably sound really cynical, and right now, I am. Some would calls this "reverse culture shock," which is probably self-explanatory. It means that after the shock of getting used to Indian culture, I'm having trouble adjusting to my own (former, pre-existing) way of life. I thought that was silly--it can't be that difficult to bounce back to the life you've been living for 24 years (give or take several weeks of travel a year)--but it actually is.

India had a great impact on me. I made connections, thanks to CFHI, with several NGOs that with God's help, I hope to revisit one day. I'd like to establish a care home or a clinic of my own there one day, and slowly but surely build it up and more importantly build up the human capacity to sustain it. Eventually, after it's self-sufficient, I will simply be a frequent visitor, a benefactor, a consultant. I will have moved on to the next project, training new people to care for their communities. It's a dream.

Meanwhile, does it make a difference to the pollution-filled beaches I saw in Mumbai, whether or not I recycle my thin plastic goods? I don't know. But I'm going to keep pushing myself to remember what I experienced in the old country, and to change my actions to reflect a better appreciation of the impact of less fortunate circumstances. Because it's not just the poor countries and the rich countries for themselves these days. What we do affects everyone. And even now, even with our botched foreign policy and inadequate homeland security, nowhere is the previous maxim more true than in the U.S. That comes from the mouths of Indians.

Friday, July 20, 2007

Friday, July 13, 2007

The end of my adventures (well, 2007's, anyway)

I'm sitting in the Delhi airport waiting for my flight to Taiwan. It hasn't really struck me that this adventure of almost two months is pretty much over. I am already itching for the next journey, not just the next public health adventure, but also my next trip to the motherland.

Completing my clinical hours for the MPH degree has opened up another world for me. When I was in class, I was always painfully aware that all that book learning gave me only a lopsided view of what it means to be a public health worker. Now I know better.

What does it entail, then? Well, during my clinical hours here in India, I saw that being a social worker/public health worker means being a teacher, a mother, a friend, a coach, and an entertainer. It requires you to sing songs to make friends with grubby kids. It requires you to teach the alphabet to and play Simon Says with middle-aged addicts. It requires you to stretch yourself so you inhabit a world that may be foreign to you, but that is everything to the people you are working with. That world is what they have; you must, in some way, own it too.

I keep telling myself that I don't need to travel halfway across the world to do this, to connect with people who need me, whose warmth and openness are probably a result of the simple, barebones lives they lead. There is plenty of field work right in my backyard, plenty of work for me to roll my sleeves up and get dirty for, which is what I like to do. I guess discovering this about myself reassures me that I've chosen the right career path for myself; being a public health worker (and I consider physicians to be public health workers, in some sense) is front line work.

Sometimes I wonder whether my experiences abroad (in Ecuador and India, to be specific) are really going to be useful to my future "target populations". I'm not sure if they will be. Could I see myself singing to addicts at a de-addiction center in the United States? Would they even respond to that? The American in me is dubious, but the human in me says why not? People are people, and perhaps there are some aspects of other cultures that could enhance my work at home in the U.S. Perhaps my parents' culture is protective against public health menaces (I think in some ways it is, but that's another post). But it's not just that. I hope to revisit the places I saw here in Bharat when I have more skills to offer. By God's grace, I've built a bridge now for myself, made contacts and put names, faces, and organizations on my internal map in a way that I'd never done before, not even in Ecuador.

Now if I could just learn Hindi!

Completing my clinical hours for the MPH degree has opened up another world for me. When I was in class, I was always painfully aware that all that book learning gave me only a lopsided view of what it means to be a public health worker. Now I know better.

What does it entail, then? Well, during my clinical hours here in India, I saw that being a social worker/public health worker means being a teacher, a mother, a friend, a coach, and an entertainer. It requires you to sing songs to make friends with grubby kids. It requires you to teach the alphabet to and play Simon Says with middle-aged addicts. It requires you to stretch yourself so you inhabit a world that may be foreign to you, but that is everything to the people you are working with. That world is what they have; you must, in some way, own it too.

I keep telling myself that I don't need to travel halfway across the world to do this, to connect with people who need me, whose warmth and openness are probably a result of the simple, barebones lives they lead. There is plenty of field work right in my backyard, plenty of work for me to roll my sleeves up and get dirty for, which is what I like to do. I guess discovering this about myself reassures me that I've chosen the right career path for myself; being a public health worker (and I consider physicians to be public health workers, in some sense) is front line work.

Sometimes I wonder whether my experiences abroad (in Ecuador and India, to be specific) are really going to be useful to my future "target populations". I'm not sure if they will be. Could I see myself singing to addicts at a de-addiction center in the United States? Would they even respond to that? The American in me is dubious, but the human in me says why not? People are people, and perhaps there are some aspects of other cultures that could enhance my work at home in the U.S. Perhaps my parents' culture is protective against public health menaces (I think in some ways it is, but that's another post). But it's not just that. I hope to revisit the places I saw here in Bharat when I have more skills to offer. By God's grace, I've built a bridge now for myself, made contacts and put names, faces, and organizations on my internal map in a way that I'd never done before, not even in Ecuador.

Now if I could just learn Hindi!

You Gotta Follow Through

Okay, I admit it. It was an amateur mistake to believe that things would go smoothly when I found a donor to buy an x-ray machine for one of the care homes we visited in Delhi. But it seemed so simple. Wire the money to the NGO spearheading the project, and they buy the machine they expressed a dire need for. Simple, right?

Wrong. And now I'm kicking myself for it because one of the major themes of my two months learning about social work/public health here in India is that follow-through is severely lacking. Yet, I feel personally affronted by this (probably predictable) episode.

To give the care home people the benefit of the doubt, it is possible that what they say is true. They claim that now that this large sum of money has come to them, there are even more pressing and more basic needs than an x-ray machine, one of which is an "auto-analyzer" (I don't know what that is but hey, I'm not a doctor yet). This is plausible. When an NGO starved for funds and always scraping to make ends meet suddenly comes into thousands of US dollars (which goes a LONG way in my mother country), lots of needs compete for those funds. Perhaps something beat out the x-xray machine...like the auto-analyzer?

Either way, it's a shady business. I appreciate the fact that the director of the care home emailed me to notify me that the money would be used in a different way. When lives are hanging in the balance, it is important to think very carefully of how to manage limited funds. Who am I to argue? But at the same time, donors have a responsibility and a right to figure out where there money is going, and when it is earmarked for a specific project, it should go there. If it's not going to go to the project you were campaigning for to begin with, don't bother telling donors what exactly you're going to do with their money...be vague enough to end up telling the truth no matter where the funds end up going.

Not surprisingly, I don't agree with the new trend of NGO online stores that let donors purchase a heifer (or a share of a heifer), or two square kilometers of irrigated land, or a can of worms for fishermen. You probably know which organizations I'm referring to. The first time I bought a basket of chicks, I really thought that my money would go to buy several baby chicks that would be delivered to a family in need. After close inquiry, I discovered that was not the case. Rather, the lady I spoke to informed me that the basket of chicks was merely representative of the sort of thing that would be done with my funds. In reality, it was possible that my money would go to administrative costs, or some other vague necessity (not that I'm against donating money for that, these NGOs have to pay salaries and overhead somehow and that's a good cause too).

Anyway, what I'm getting at here is something else. I'm not here to complain about corruption or laziness among NGOs. I'm here to say that what I've learned here in India, big-time, is that as a public health worker, I MUST be the one to follow through. If I want to come to this country and help, the first thing I need to do is make a TIME COMMITMENT. Why didn't I go and pick out that x-ray machine myself? Because I didn't have enough time. How bad is that? If I really wanted to help, and not do a 99/100 as Paul Farmer calls it (almost, but not quite, accomplishing a necessary task), I would have ensured that the money was used wisely by putting my own sweat and blood into it.

God willing, that's exactly what I intend to do from now on. Let this be a lesson.

***Update: I called up the care home today, to inquire about what happened with the donated money. Apparently, there had been some miscommunication initially, and all along, it was an auto-analyzer, not an x-ray machine, that had been needed. As luck would have it I came down with my second case of mild food poisoning last night, so I wasn't up to schlepping around (it's at least a 45-minute drive) in the Delhi heat. I talked to the workers there, and they assured me that the auto-analyzer had been bought, and it was greatly needed. It apparently allows them to run 300 lab tests a day, and is useful for all patients, whereas the x-ray machine would have benefited only possible TB patients (a large percentage of HIV/AIDS patients, but not ALL of them).

I still have some questions. For example, there are only 26 beds in the care home; do they really need the capacity to do 300 lab tests a day? I'm not questioning their needs, simply trying to be a responsible donor. If one of the major problems with public health today is lack of leadership and management, I figure I have to do my part by seeing things through to the end.

Wrong. And now I'm kicking myself for it because one of the major themes of my two months learning about social work/public health here in India is that follow-through is severely lacking. Yet, I feel personally affronted by this (probably predictable) episode.

To give the care home people the benefit of the doubt, it is possible that what they say is true. They claim that now that this large sum of money has come to them, there are even more pressing and more basic needs than an x-ray machine, one of which is an "auto-analyzer" (I don't know what that is but hey, I'm not a doctor yet). This is plausible. When an NGO starved for funds and always scraping to make ends meet suddenly comes into thousands of US dollars (which goes a LONG way in my mother country), lots of needs compete for those funds. Perhaps something beat out the x-xray machine...like the auto-analyzer?

Either way, it's a shady business. I appreciate the fact that the director of the care home emailed me to notify me that the money would be used in a different way. When lives are hanging in the balance, it is important to think very carefully of how to manage limited funds. Who am I to argue? But at the same time, donors have a responsibility and a right to figure out where there money is going, and when it is earmarked for a specific project, it should go there. If it's not going to go to the project you were campaigning for to begin with, don't bother telling donors what exactly you're going to do with their money...be vague enough to end up telling the truth no matter where the funds end up going.

Not surprisingly, I don't agree with the new trend of NGO online stores that let donors purchase a heifer (or a share of a heifer), or two square kilometers of irrigated land, or a can of worms for fishermen. You probably know which organizations I'm referring to. The first time I bought a basket of chicks, I really thought that my money would go to buy several baby chicks that would be delivered to a family in need. After close inquiry, I discovered that was not the case. Rather, the lady I spoke to informed me that the basket of chicks was merely representative of the sort of thing that would be done with my funds. In reality, it was possible that my money would go to administrative costs, or some other vague necessity (not that I'm against donating money for that, these NGOs have to pay salaries and overhead somehow and that's a good cause too).

Anyway, what I'm getting at here is something else. I'm not here to complain about corruption or laziness among NGOs. I'm here to say that what I've learned here in India, big-time, is that as a public health worker, I MUST be the one to follow through. If I want to come to this country and help, the first thing I need to do is make a TIME COMMITMENT. Why didn't I go and pick out that x-ray machine myself? Because I didn't have enough time. How bad is that? If I really wanted to help, and not do a 99/100 as Paul Farmer calls it (almost, but not quite, accomplishing a necessary task), I would have ensured that the money was used wisely by putting my own sweat and blood into it.

God willing, that's exactly what I intend to do from now on. Let this be a lesson.

***Update: I called up the care home today, to inquire about what happened with the donated money. Apparently, there had been some miscommunication initially, and all along, it was an auto-analyzer, not an x-ray machine, that had been needed. As luck would have it I came down with my second case of mild food poisoning last night, so I wasn't up to schlepping around (it's at least a 45-minute drive) in the Delhi heat. I talked to the workers there, and they assured me that the auto-analyzer had been bought, and it was greatly needed. It apparently allows them to run 300 lab tests a day, and is useful for all patients, whereas the x-ray machine would have benefited only possible TB patients (a large percentage of HIV/AIDS patients, but not ALL of them).

I still have some questions. For example, there are only 26 beds in the care home; do they really need the capacity to do 300 lab tests a day? I'm not questioning their needs, simply trying to be a responsible donor. If one of the major problems with public health today is lack of leadership and management, I figure I have to do my part by seeing things through to the end.

Saturday, July 7, 2007

Right in my backyard: Dharavi, a US $665 million industry (and Asia's biggest "slum")

Two days ago, thanks to Sej's thorough research on Bombay last year, I went on a tour given by a company called Reality Tours and Travel. The tour was not of Colaba, or Haji Ali Pier, or the Gateway of India, but of Dharavi, the place famously known as Asia's biggest slum.

Sej and I had been looking forward to going on this tour for months (no worries, she vows to see it next time). We knew it was not just a slum, but an area buzzing with industry. The combination of poverty (or low income) and industry is particularly interesting to us as public health enthusiasts.

I met Davindra, my tour guide, at the Mahim train station in Bombay. I had no idea where we were going, but it turned out that the station was merely a meeting place; Dharavi is within minutes of Mahim.

Davindra is a slight teenager from a Gujarati family. He immediately tells me that he lives in Dharavi. He's studying "b comm" which will earn him a bachelors in business (commerce). He is the eldest of four children, and his three siblings are girls. When I recount these facts to my aunt, with whom I'm staying not twenty minutes from Dharavi (but worlds apart), she and her friend cluck sympathetically for Davindra's parents, who have been saddled with the financial responsibility of three girls.

But this tour isn't about Davindra, as curious as I am to know about his life. He's very knowledgeable about Dharavi; he was picked and trained by the travel agency for his friendliness and relative ease with the English language.

While many people call Davindra's home a slum, it's really not (and he is quick to tell me so). Dharavi takes up 432 acres of land in an excellent location of Bombay, close to the financial sector and the residential sector, as well as the seaface. There are officially (read: government-recognized) about 60,000 families living here, but the true number, Davindra says, is actually 900,000.

We make our way to the rooftop of one of the slum buildings, where plastic waste is being melted and reformed into little green pellets to sell as raw material. I see groups and groups of people on each roof, working with plastics, socializing, looking at us...everyone doing something. No one is sitting idle.

Davindra tells me as we survey all the activity around us that Dharavi is currently being threatened by a bid to turn the area into a special economic zone. Will it happen, I ask? He has no idea, but tells me that while the government promises to relocate families, it will be difficult (to say the least) for all these workers to shift their businesses and families to new locations. He recalls the government's vow to rehabilitate slum areas by 2005; they failed miserably. Despite this, a few Dharavi dwellers are supportive of the special economic zone project, somehow believing that they will be among the tiny fraction of those who will receiving new housing.

Throughout the tour, I see factories dedicated to making soaps, snacks, pots, and clothing. Recycling is an important industry in Dharavi, so after garbage is sorted by ratpickers, plastic trash is sold here to be reprocessed. The money Dharavi residents spend on buying plastic garbage, they recoup by selling remanufactured plastic pellets. They also recycle tin cans and barrels, peeling off labels, heating them up, and banging them back into shape before reselling them to various companies. This "slum" is also where ALL Mumbai leather comes to be tanned.

The tour continued with a stop to the school funded by Reality Tours and Travels, where slum children learn English (Davindra tells me that Dharavi parents know how important education is, and push their kids to complete at least a basic education). It ended with his inviting me to his own home, which is in the pottery area of the slum, dominated by families that migrated from Gujarati a couple generations back. His home is neat and tidy (it's literally as big as a hallway), and his mother and sister are napping on the floor in the kitchen. The home has tiled floors, painted walls, electricity, a ceiling fan, a TV, and a refrigerator. It is undoubtedly super-cramped, but it's not a slum dwelling by any stretch.

I don't know what will happen to Dharavi...will the special economic zone pushers win? I'm very wary of "slum rehabilitation" projects. I can see why it's frustrating that Dharavi takes over prime real estate in a city like Bombay (where some apartments are more expensive, per square foot, than anywhere else in the world), but if public health was more of a priority, maybe the first low-income families would not have felt the need to settle here back in the 1860s, when Dharavi was nothing more than a landfill.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Today's headlines: How it is for the average poor female

I was bitterly surprised to read a quote by a famous Bollywood actor in the newspaper who claimed that the plethora of curvaceous female role models in the film industry is indicative of the improvement of women's status in Indian culture. Have they stepped out of their posh homes to see what the rest of India is like?

Thanks to my wandering through India this summer, I have. And women's status has indeed been improving in scattered areas as a result of the hard work of a few NGOs (I'm not going to get started on the ample corruption that clouds such efforts, just the ones that actually get something DONE for the target communities).

You don't have to travel three hours in a bumpy, overcrowded bus or tour destitute villages to get a taste of what it means to be a low-income female in this country. Just pick up the paper every day, and you'll soon find out.

Some of today's related news (I've been reading the paper for weeks now, this is typical):

-22-year old girl is harrassed for dowry and for bearing a female child, so she protests the mental and physical abuse she has suffered from her in-laws by walking around Gujarat in her underwear. Upon arriving at the police station, she tries to immolate herself as a demonstration but is restrained.

-2-day-old infant is found buried alive in Andhra Pradesh by her grandparents, because she is the seventh girl in the family.

-Due to unclear laws on the legal age of marriage for a girl in India, 15-year-old girls are being coerced into marriage. High Courts refuse to press rape charges, ruling that the 'age of discretion' has been reached at 15 years of age. No law fixing the uniform age for consensual sex exists.

-26-year-old girl working as a domestic help is brutally stabbed by her 22-year-old lover nine times with a pair of scissors, because she refused to continue the 'relationship' (the other day, a young, pregnant woman was bludgeoned to death by her lover as bystanders looked on, doing nothing. By the time someone finally put her into a rickshaw and sent her to the hospital, it was too late. She was killed for insisting that her lover marry her after discovering she was pregnant).

So no, famous Bollywood stars, things are not necessarily changing for the average poor woman in India, and they are certainly not changing because of how strong, sexy, rich and wholesome Bipasha Basu, Kareena Kapoor, Rani Mukherjee and Aishwarya Rai are.

Thanks to my wandering through India this summer, I have. And women's status has indeed been improving in scattered areas as a result of the hard work of a few NGOs (I'm not going to get started on the ample corruption that clouds such efforts, just the ones that actually get something DONE for the target communities).

You don't have to travel three hours in a bumpy, overcrowded bus or tour destitute villages to get a taste of what it means to be a low-income female in this country. Just pick up the paper every day, and you'll soon find out.

Some of today's related news (I've been reading the paper for weeks now, this is typical):

-22-year old girl is harrassed for dowry and for bearing a female child, so she protests the mental and physical abuse she has suffered from her in-laws by walking around Gujarat in her underwear. Upon arriving at the police station, she tries to immolate herself as a demonstration but is restrained.

-2-day-old infant is found buried alive in Andhra Pradesh by her grandparents, because she is the seventh girl in the family.

-Due to unclear laws on the legal age of marriage for a girl in India, 15-year-old girls are being coerced into marriage. High Courts refuse to press rape charges, ruling that the 'age of discretion' has been reached at 15 years of age. No law fixing the uniform age for consensual sex exists.

-26-year-old girl working as a domestic help is brutally stabbed by her 22-year-old lover nine times with a pair of scissors, because she refused to continue the 'relationship' (the other day, a young, pregnant woman was bludgeoned to death by her lover as bystanders looked on, doing nothing. By the time someone finally put her into a rickshaw and sent her to the hospital, it was too late. She was killed for insisting that her lover marry her after discovering she was pregnant).

So no, famous Bollywood stars, things are not necessarily changing for the average poor woman in India, and they are certainly not changing because of how strong, sexy, rich and wholesome Bipasha Basu, Kareena Kapoor, Rani Mukherjee and Aishwarya Rai are.

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

Anti-US Sentiments in the World's Most Populous Democracy

I haven't blogged for a few days as it hasn't been easy to relate shopping and bargaining and overeating to public health in any meaningful way (especially after the past month of hospitals, care homes and ARV clinics).

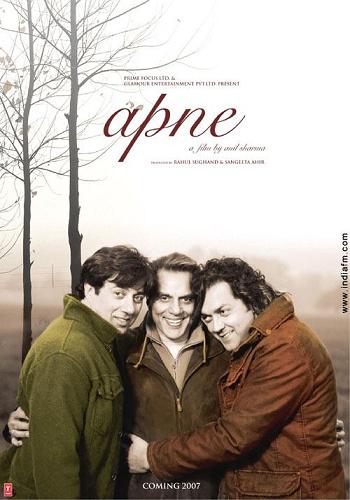

But I'm nothing if not resourceful, so I'm going to make a blog out of a Hindi film that just came out called Apne (Yours). It's about two sons who become champion Indian boxers and fight their way to the final round of the World Championships to face a killer opponent: Luca Gracia of the United States. (Luca is African-American, which seems to make him more menacing to Indian audiences)

The film is about more than boxing. It's even about more than family honor, which is all Indians need to get roped into a movie. It's about National Pride.

These Indian brothers, played by Sunny and Bobby Deol, didn't start out as boxing champs. Their father was a contender who was banned from the sport after doping charges were leveled against him. He wants to train his younger son, Bobby, to win the Asian championship and earn the privilege of fighting against Luca. When Bobby does face Luca, the U.S. athlete cheats to win, putting grease on his gloves and smearing them on Bobby's eyes (yes, Hindi movies are this dramatic...you don't know the half of it). In just 30 days, brother Bobby decides to train himself to face Luca...not just for family honor but, as I said, for the honor of the country.

Driving home this point about country honor was interesting to me. It's telling that the world champ Luca is from the U.S., and that he is portrayed as a killer opponent who cheats to win (and who has the goods to do it). Luca even tells the Indian trio (Sunny, Bobby and dad) that it doesn't matter who wins. It's not about honor, it's the money that matters.

Does this sound familiar? First of all, does this portrayal truly reflect Indian sentiment toward the U.S.? Is it just India, or South Asia in general? Is there any truth to it?

My opinion: yes, yes, and yes.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

It's all about small business

I just read in this morning's edition of The Times of India something that I've suspected for awhile: India doesn't support small business the way it should, and that fact is costly for individual and national economic welfare.

The World Bank produces rankings, judging countries by the amount governmental support is given to budding entrepreneurs. The US, a nation that has built up its economy largely on the success of small business, ranked third, after Singapore and New Zealand. Also in the top 5 are Canada and Hong Kong. India ranked 46th out of just 53 countries...China was not much better, placed at 42.

Surprised?

What is this ranking all about? Does it have anything to do with economic prowess? We are always talking about the two up-and-coming nations in Asia, China and India. How can these countries be so low on this indicator, lower on the list than Latvia, Peru and Uganda?

It's not that you don't find entrepreneurship in India. Lining every street are entrepreneurs, whether they're peddling chai, paan, AA batteries or dyed fabrics. The problem is that they are not given the financial support from the public sector to make their businesses grow. As a result, the lower-class shop/stall/booth-owner on the street is perenially unstable. Instead of moving up in life through his business, he continues to live with his family in a shack made of metal scraps, plastic sheeting and flattened cardboard boxes. He might sleep on the floor of his shop, and you'll have to wake him up in the morning if you want service. It's obvious that he isn't getting significant tax breaks, write-offs, or any other appreciable incentive to make his business (and his living standards) grow.

Why should the government care about this? Because it has no middle class whatsoever. As with everything else in this country, a multi-sectoral approach is desperately needed. If we touch one part of society/economics/politics without a comprehensive stakeholder analysis, it could have disastrous consequences. But what the World Bank rankings on country support for entrepreneurship tells me is that another element of socioeconomic well-being has been singled out, and that is small business.

Also on the news front in India: more rains, more hectares of land diverted for special economic zones (SEZs), more accidental deaths (boy falls in crack between escalator and railing; bus crashes into cars, killing child; 14 die in monsoon floods), more friction in the Gulf (although ideological brothers Iran and Venezuela are apparently cozying up over their common enemy, the US); and more attention sickeningly diverted from actual news to trashy news, all over the world (Bollywood takes precedence over public health, Paris Hilton replaces Michael Moore on Larry King Live...I think I can leave it at that).

Also interesting, but not directly related to India, is Iran's new position on rationing petrol, and the ensuing riots at gas stations. Citizens were shocked by the announcement that petrol would suddenly now be rationed before anyone, even the rich, could stock up. We fight over nuclear weapons that may or may not exist (does it even matter, given our current world issues???). I cannot imagine what chaos will ensue when we start to fight over fuel. Eventually, some good will come from it, including more rapid conversion to biofuel and other eco-friendly energy alternatives.

The World Bank produces rankings, judging countries by the amount governmental support is given to budding entrepreneurs. The US, a nation that has built up its economy largely on the success of small business, ranked third, after Singapore and New Zealand. Also in the top 5 are Canada and Hong Kong. India ranked 46th out of just 53 countries...China was not much better, placed at 42.

Surprised?

What is this ranking all about? Does it have anything to do with economic prowess? We are always talking about the two up-and-coming nations in Asia, China and India. How can these countries be so low on this indicator, lower on the list than Latvia, Peru and Uganda?

It's not that you don't find entrepreneurship in India. Lining every street are entrepreneurs, whether they're peddling chai, paan, AA batteries or dyed fabrics. The problem is that they are not given the financial support from the public sector to make their businesses grow. As a result, the lower-class shop/stall/booth-owner on the street is perenially unstable. Instead of moving up in life through his business, he continues to live with his family in a shack made of metal scraps, plastic sheeting and flattened cardboard boxes. He might sleep on the floor of his shop, and you'll have to wake him up in the morning if you want service. It's obvious that he isn't getting significant tax breaks, write-offs, or any other appreciable incentive to make his business (and his living standards) grow.

Why should the government care about this? Because it has no middle class whatsoever. As with everything else in this country, a multi-sectoral approach is desperately needed. If we touch one part of society/economics/politics without a comprehensive stakeholder analysis, it could have disastrous consequences. But what the World Bank rankings on country support for entrepreneurship tells me is that another element of socioeconomic well-being has been singled out, and that is small business.

Also on the news front in India: more rains, more hectares of land diverted for special economic zones (SEZs), more accidental deaths (boy falls in crack between escalator and railing; bus crashes into cars, killing child; 14 die in monsoon floods), more friction in the Gulf (although ideological brothers Iran and Venezuela are apparently cozying up over their common enemy, the US); and more attention sickeningly diverted from actual news to trashy news, all over the world (Bollywood takes precedence over public health, Paris Hilton replaces Michael Moore on Larry King Live...I think I can leave it at that).

Also interesting, but not directly related to India, is Iran's new position on rationing petrol, and the ensuing riots at gas stations. Citizens were shocked by the announcement that petrol would suddenly now be rationed before anyone, even the rich, could stock up. We fight over nuclear weapons that may or may not exist (does it even matter, given our current world issues???). I cannot imagine what chaos will ensue when we start to fight over fuel. Eventually, some good will come from it, including more rapid conversion to biofuel and other eco-friendly energy alternatives.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)